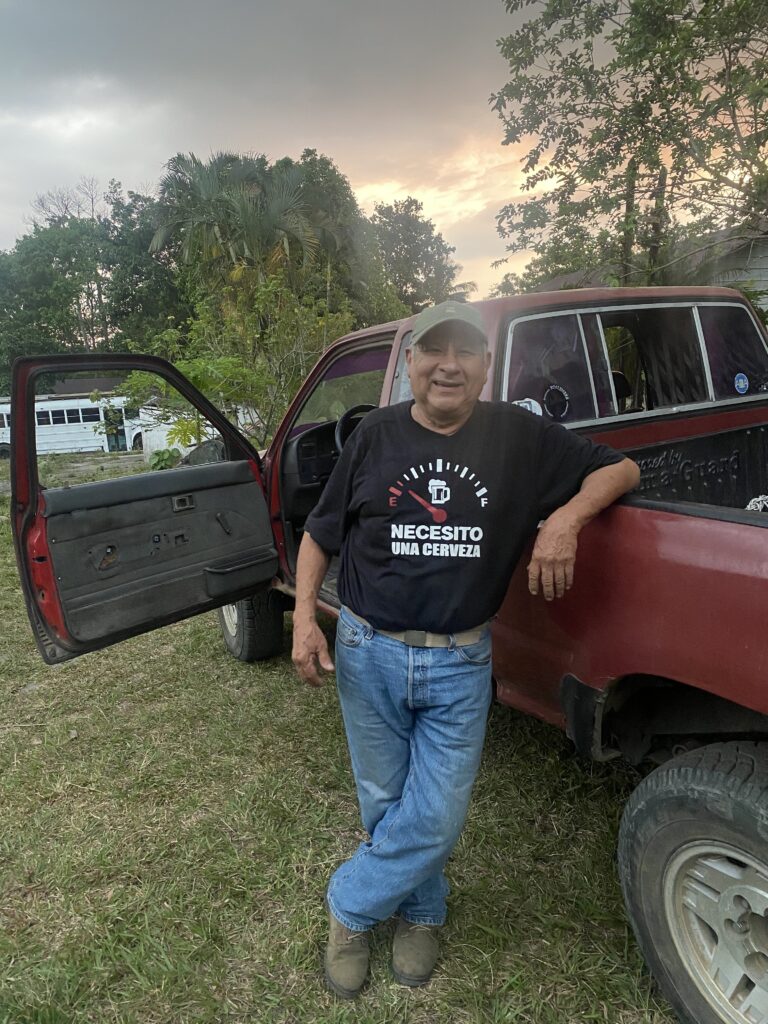

Tío Chalo / Chicacao, Guatemala, Feb 2025

On every corner in Chicacao, someone knows him. They call him “Chalo,” “Tío,” or just shout his name like they’re calling an old friend across a lifetime. And if Tío Chalo had run for mayor, he’d have won by a landslide. But he never would. The very suggestion made him roar with laughter, his eyes crinkling in that way that made you forget time. “Why would I want more problems?” he’d say, throwing his hands up. “I already produce three things here: coffee, bananas, and problems.”

Tío Chalo was a man with a laugh like a bonfire—warm, unconfined, and capable of pulling everyone into its glow. You could hear it echo down the street even before you saw him, always surrounded by people. He had a way of drawing them in, a magnetic pull stronger than the Guatemalan sun. And he gave freely: fruit from his farm, advice laced with humor, and—of course—beer.

He was always drinking one, buying one, or talking about one. “Do you know where the Mayans come from?” he asked me once, mid-sip. I opened my mouth, ready for a history lesson, but he beat me to it. “Miami!” he said, grinning, and his laugh bubbled up like a spring.

One afternoon, when we were supposed to be grocery shopping, Tío Chalo invited us to his house. “Come,” he said simply, “Come to my house,” waving us in as though he had known us all his life. “You’re welcome here.” And he meant it. That’s the thing about Tío Chalo—when he says you’re welcome, you truly feel it.

His farm was a paradise, a place that felt untouched by time. Chicacao had long since turned to rubber trees and other crops, but not Chalo. His land was a symphony of colors and smells: bananas hanging heavy from trees, Chicos scattered like jewels on the ground, soursop interspersed throughout, and coffee plants standing proud in the sun. Everything grew freely, without sprays or chemicals. “It’s real fruit,” someone whispered to me. “The way it used to be.”

Inside his home, the table was a riot of flavors: ripe fruit spilling over the edges, plates of food passed from hand to hand, and—of course—banana bread. Someone had given it to Chalo as a thank-you for bananas he’d gifted them earlier. Now, we all ate it, the sweetness mingling with laughter and beer. He asked us to determine which of his neighbors made the best banana bread.

When the sun began to set, we lit a fire outside. Someone started playing music, and before long, we were dancing, singing, and even shooting at beer bottles lined up on a log. The night felt endless, like a dream where time slips through your fingers, soft and golden. Alejandro, one of Chalo’s nephews, presented a small Mayan relic he’d found in the fields to a couple named David and April, to celebrate their engagement. It was a simple gesture, but it carried the weight of history, as though the land itself partnered in its generosity through him.

As the spontaneous fiesta continued on, Chalo’s jokes carried us through the night, binding us together like family. You didn’t need to be blood to belong to him.

When it was finally time to leave, we all piled into the back of the truck, drunk on beer and joy. The road to Arabia stretched out before us, the silhouettes of palm trees cutting against the glittering stars. Someone turned on music, and we sang loudly, our voices rising into the night. “Man,” Dave said, leaning back with a smile, “this is one of those memories that’s never going to go away.”

It would have been easy to forget we had started this day shopping for groceries–and a lot of them. Eventually arriving at Arabia late in the night, there was no question of just dropping us off with the groceries and leaving. We all unloaded the truck together, moving like a single organism. Chalo led the way, singing and dancing as he carried boxes, his laugh punctuating the rhythm. Even in work, there was joy.

By the time we finished, the night was quiet again, but the glow of Chalo’s fire still burned in all of us. He is a man wrapped in mystery, with a history I can’t begin to understand, but it doesn’t matter. Chalo’s magic wasn’t in the details of his past—it was in the way he made everyone feel, and how integral he was in bringing people from all over together so effortlessly.

In Chicacao, Tío Chalo was a legend. But to us, and no matter for how long we had known him (I, for example, only spent two weeks at the farm), he was quickly family. And in his laughter, his generosity, and the simple beauty of his life, we found something rare and unforgettable: the kind of belonging that stays with you, even after you leave.

The day I left Arabia, Chalo and another friend, Thomas, took me to the bus before they went grocery shopping, naturally. Tío Chalo handed me a plastic bag full of heavy discs of pure Cacao from his farm, “you’ll need this to stay warm at night in Xela. Cold there. These are my best, not cut with sugar, you’ll love them.” I was elated by the gift, already looking forward to my first cup of hot cacao in my next home. They waited there until the bus driver climbed in to start driving, and waved at me as we rumbled away, that soft smile and crinkled eyes being the perfect sendoff as I left the jungle.

![Vignettes by V [and other miscellany] logo](https://vignettesbyv.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/C96F28F1-618C-41EB-832A-E04D4A6EC68D.png)

![Vignettes by V [and other miscellany] logo](https://vignettesbyv.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/C96F28F1-618C-41EB-832A-E04D4A6EC68D-300x300.png)